The Problem of Wild Animal Suffering for an Ethical Vegan

I am a vegetarian (sinning vegan) with a deep love for the natural world. I wrote this to clarify my thinking on my own obligations towards wild animals. I wrote this piece as a final submission to a course on environmental ethics at Wageningen University convened by Prof Bernice Bovenkerk.

The problem of wild non-human animal suffering raises difficult questions for the ethical vegan or vegetarian. A vegan’s obligations toward wild animals is sometimes even posed as an absurd implication and thus refutation of veganism.1 Vegans have differing philosophical justifications for their veganism; justifications which imply divergent obligations towards wild animals. In this post, I explore the ethical implications for wild animals implied by three theories that ethically require veganism: hedonic utilitarianism, antinatalism, and citizenship theory. This post does not consider sustainability as a justification for veganism. I find that utilitarianism may imply extensive obligations towards wild animals, that antinatalism favours the non-existence of wild animals, and that citizenship theory may provide intuitively attractive grounds for non-intervention.

Background

For the purposes of this paper, wild demarcates low direct dependence on humans for the proximate and continued existence of the non-human animal and low levels of habituation.2 It is beyond the scope of this paper (and not possible) to define wild to capture all intuitions. It certainly includes animals that live in nature reserves that would not exist without the protection of humans (such as Kruger National Park), while excluding both pets and all agricultural animals. For the purposes of this paper, in default, ‘animals’ refers to sentient animals, those we might suppose there ‘is something it is like to be’,3 for example all mammals, but probably not sea sponges.

The problem of wild animal suffering is often analysed through the lens of predation. Predation does cause immense suffering, without commensurate pleasure, as wryly observed by Schopenhauer.4 However, it is also one of the least tractable examples of wild animal suffering as it requires the consideration of competing non-human animal interests5 and often leads to confusion about the culpability of the predator6 vs culpability or responsibility of the intervening human or would be ‘Good Samaritan’. Lastly, ecosystems are often in a precarious homeostatic balance in which predators hold a very important role in balancing trophic levels; a role non-experts can underappreciate.7

Finally, many vegans are self-described ‘nature-lovers’, which can lead to a romanticisation about the lives of wild animals. There are many quotes by eminent biologists and philosophers describing the blind cruelty of nature. Yet, the abundance of wild animal suffering is ubiquitous, as I experienced on my most recent visit to Hlulhluwe-Umfolozi National Park, in KwaZulu-Natal South Africa, one month ago.

A severe drought had led to the starvation of hundreds of animals outside the park (where water was not artificially pumped), a death most cruel. This drought was terminated by flooding, leading to many more, yet mostly invisible deaths, including of several local human villagers. One death was that of a zebra mother who had died from a lightning strike—her tick-infested baby circling her rigor mortis body.

The flooding will likely lead to a population explosion of herbivores due to flourishing pasture. These populations will ultimately be decimated by either predation, Malthusian8 overgrazing, or another drought: the boom-and-bust cycle of life. Indeed, immense suffering is caused by life itself being dictated by selfish genes. Many species produce large surpluses of sentient offspring, as most will quickly perish, the r-selection evolutionary strategy.9 Political philosophy is replete with theories with the premise that the goal of political organisation and justice is to escape the “state of nature”. For good reason. It is thus plausible that we should do something to reduce this immense wild animal suffering.

Hedonic Utilitarianism

The first ethical justification for veganism I consider is hedonic utilitarianism. This is the theory that being ethical entails acting to maximising the sum10 of positive brain states, or pleasure, while minimizing the sum of negative brain states, or suffering (negative and positive defined by the subjective experience of these states, with positive and negative perfectly commensurable).11

Veganism is clearly ethically required by this theory: the suffering induced from raising and slaughtering non-human animals is significantly greater than the pleasure or gain (typically only from flavour) of eating non-human animal flesh. Thus, the question for the hedonic utilitarian vegan is:

Can I reduce the suffering of wild animals without causing more suffering to myself or other sentient beings?

This theorem could lead to extensive obligations as the suffering of wild animals appears to be vast. Some vegan utilitarian philosophers, such as Peter Singer, have at times attempted to side-step this issue. They have claimed that although we would have extensive obligations could we reduce wild-animal suffering, the fact of the matter is that intervention is more likely to create more suffering than it reduces.12

This is related to the epistemic claim that we might be able to reduce wild-animal suffering, yet we do not know how to (at least currently). Or, at a minimum, in complex systems such as ecosystems, the probability of unintended consequences is significant. Since we do not know how to reduce wild-animal suffering, the hedonic utilitarian vegan has no obligations toward wild animals.

The above claims about limited capacity are an important consideration. For example, herbivore populations could explode if prey animals are removed from a wild area. This could lead to overgrazing and ultimately the deaths of a similar number of herbivores as those from predation. Wild population sizes are ultimately dictated by Malthusian dynamics. Yet, these examples describe a gap in current knowledge, not an immutable pattern of wild animal suffering. Utilitarianism could thus demand further research into reducing wild animal suffering, as per the burgeoning field of welfare biology. 13

The Parfit utilitarian (discussed at length in the next section) might still favour animals being brought into existence and then dying (perhaps even painfully). The Parfit utilitarian would favour as many animals existing as possible, so long as the positive total utility implied by a large number of existent beings is greater than the total disutility. Under natural environmental circumstances, this is implausible as there is often zero-sum competition for resources. Finally, there could be unintended consequences, and irreversible tipping points, such as overgrazing leading to erosion and thus a reduction in total grazeable land, something which would both reduce total population and lead to starvation.14

Nonetheless, there do seem to be ways we could reduce wild-animal suffering on net. Some game farms are inoculating feeding troughs with antiparasitic medication.15 This can prevent not only a gruesome form of death but also allow the lives of animals to improve. Some parasites can live in/on the body for a long time16 leading to everything from gangrene to blindness, and ultimately death. Eliminating the parasite can lead to welfare improvement without major alterations in population dynamics.

Whether there would be unintended consequences of doing this for all wild mammals is an empirical question. Nonetheless, it suggests to me that there are some aspects of wild animal suffering which can be reduced. This could plausibly be accomplished through donating to charities providing wild animals with these antiparasitic medications, thus entailing an obligation, should the cost be low enough.

A further impediment to acting on the suffering of wild animals for the utilitarian is the opportunity cost of that action. Veganism typically comes at no commensurate cost to the lives and suffering of sentient beings. However, solving some of the complex issues that lead to wild animal suffering might be rather costly.

We have seen how a lack of artificial water sources leads to large busts in wild animal populations outside of game parks. Providing a wild area with water (from boreholes or otherwise) could plausibly improve the welfare of wild animals by reducing the variance in population sizes. However, it could cost the same or more as providing water to a nearby human community, many of which are still lacking. Antiparasitic inoculation could likewise be compared to vaccinating children. When the opportunity cost of these interventions is helping people, the right thing to do becomes less clear for the hedonic utilitarian.17

Does wildness matter for a hedonic utilitarian?

The above practical matters for the utilitarian are also accompanied by a more conceptual problem. I have shown how ecosystems and the populations within them are defined by some inherently cruel dynamics, such as Malthusian population limitation and the r-selection strategy. I have shown how partial intervention in ecosystems often cannot alter these dynamics and indeed might reinforce them leading to worse utility outcomes. However, humans are becoming more powerful and technologically advanced and thus there is the consideration at the other end of the spectrum: total control.

This invites a thought experiment. Suppose we create a manufactured environment for sentient wild animals designed to eliminate suffering as much as possible. All mice babies will live to reproductive age, and thus we have fed them a fertility limiting hormone—such that they only have 2 offspring, equalling replacement. All predators are fed on lab-grown meat and have had their hunting drive stimulated by artificial animals, et cetera. This is now (by stipulation) a utility maximising environment for the animals within. However, we are surely no longer speaking of wild animals.

This is not an inherent problem for the utilitarian; they have no special obligations to wildness that, say, a deontologist might have. However, there may still be a significant utility cost. Many people (including myself) appear to need to experience nature and wildness in order to maintain personal happiness. It might not directly require that many more mice are produced than will live, but the gestalt of wildness must remain and seems easily perturbed (I quickly notice when vegetation becomes alien and species composition changes nearer to urban centres).

What might be the basis of this positive experience? And can this experience be generalised to humankind? Humans are not disembodied minds. We are animals who have evolved embedded in pristine environments. Using our evolved capacities in these environments may be a high utility experience. As love for another is an evolved capacity, so too is using our bodies and minds to move through and exist in natural environments. This echoes Nausbaum’s capabilities approach.

Aesthetic experiences are likewise of high subjective utility. Manmade artefacts can be extraordinarily beautiful. However, an appreciation of beauty must likewise be an evolved capacity. The origins of the capacity for aesthetic appreciation are deeply embedded in the environments in which they (we) evolved. Pattern recognition evolved for foraging but now gives meaning to abstract art. The satisfaction of locating a mushroom amongst leaf litter is much like the experience of getting lost in a textural swath of a Kandinsky.

Wild areas and species have at minimum a substantial aesthetic value, greater than all the world’s human art. There is something deeply fulfilling, atavistic, to the experience of a campfire next to a river; a clear stary night; the more-silent-than-silence of the sound of wind flowing through trees. The most trite and poetic truths are sometimes also the most fundamental. There may not be a god, but we were created nonetheless, by evolution, as dictated in part by environmental selection. It stands to reason that we might distinctively relate to that which created us at the biological scale.

This ties the intuition of Aristotelian ethics with the hedonic experience of using one’s innate capacities. Martha Nussbaum likewise forwards an argument of ‘the good’ as capability fulfilment.18 However, identifying humans as evolved animals, which ties these capabilities to our genetic essence, provides the force behind the claim that this utility is universalizable. As per Nussbaum, a hedonic-capabilities approach pertains to non-human animals too. Can a pod of whales experience the good life in any current circumstances which are not wild? I think not. If this extends to many non-human animals, the utility of the supposed utility maximising non-wild environment might necessarily be negative due to the constraints of the evolved mind.

This is distinct from the claim that that which is natural is necessarily good. The evolutionary mechanisms previously described are natural yet induce vast suffering. The human fist has likely evolved to punch other humans.19 Using this capacity is typically of negative utility because it typically harms others. However, in controlled environments, for example in martial arts, people can experience immense utility from exploring this otherwise ‘negative’ capacity. Thus, the naturalist fallacy lies on one end of the spectrum: denying the evolutionary origins of our mind, pleasure and pain, on the other. Ultimately, the degree and universalizability of the pleasure induced by natural environments is an empirical question and thus lies beyond the scope of this paper.

I have argued that experiences of wildness may be of substantial hedonic utility due to the link between natural environments and our evolutionary origins. However, the utilitarian needn’t accept our or other animals’ evolutionary origins as immutable. This invites an alteration of the original thought experiment. Rather than changing environmental conditions, it is plausible that an animal could be created which experiences maximum (or even simply positive marginal) utility in most environments. The hedonic utilitarian might achieve this through genetically modifying sentient beings to this end. Indeed, a utilitarian would favour the creation of as many utility optimising beings as is possible. This would effectively replace natural selection as the creator, with genetic science and mankind as the creator.

This thought experiment operates similarly to Robert Nozick’s Experience Machine thought experiment:20

Suppose there were an experience machine that would give you any experience that you desired. Superduper neuropsychologists could stimulate your brain so that you would think and feel you were writing a great novel, or making a friend, or reading an interesting book. All the time you would be floating in a tank, with electrodes attached to your brain. Should you plug into this machine for life, preprogramming your life's experiences?

Many reject hedonism on the basis that they would not choose to enter the experience machine where only hedonic pleasure is gained, at the expense of reality. Likewise, the idea of creating beings which experience environment independent pleasure may strike many as absurd or impossible. If the moral value of these beings is thought to be absurd, it is hedonic utilitarianism itself that is under threat. However, intuitions are perhaps unreliable indicators of moral truth at this degree of situational contrivance.

This is perhaps best demonstrated by a reversal of the Experience Machine.21 Imagine instead that you are already in the Experience Machine, memories of base reality removed. Life is not blissful pleasure due to the constraints of your evolved brain. However, for your brain, the reality you currently inhabit is optimised for whatever pleasure your brain is capable of. Now you are asked if you would like to return to ground reality where you would suffer substantially more. Most would surely choose to continue living their ‘artificial’ lives. Perhaps likewise we really do have a responsibility to breed pleasure maximizing beings.

Conclusion

This section began by showing that hedonic utilitarians may have extensive obligations to wild sentient non-human animals. However, these obligations are constrained by both capacity and knowledge about how to improve the lives of wild animals. This suggests greater attention to the field of welfare biology is needed. However, the utilitarian must also weigh the opportunity cost of any intervention for wild animals against an equivalent expense towards improving the welfare of humans or domesticated animals. Finally, whether wildness matters for the utilitarian is considered. Here a novel thought experiment is presented, showing that the utilitarian might have an obligation to maximise the production of genetically modified organisms which experience net pleasure. Whether this is persuasive for the utilitarian, or provides grounds for not ascribing to utilitarianism, is left to the reader.

Antinatalism

David Benatar’s antinatalism is discussed in this section.22 Benatar’s antinatalism is primarily concerned with the permissibility of procreation. However, Benatar also believes his axiology extends to sentient non-human animals. Benatar has not written extensively on his theory’s implications for wild animals. This section seeks to analyse antinatalism’s implications for wild animals, starting with a description of the theory.

Figure 1. 23

Antinatalism begins with an analysis of value, purporting to show an inherent asymmetry in value between existence and non-existence. Figure 1. is reproduced for clarity. On the left-hand side, X (a human or non-human animal for our purposes) is brought into existence. It is uncontroversial (at least relatively), that when X experiences pain, that is bad, and when X experiences pleasure, that is good (first column). Prior to Benatar’s theory, the (relevant) prevailing theory was that in order to determine whether a life is worth bringing into existence, one should estimate whether that being will experience, on net, more pleasure than pain, i.e., determine whether the good will outweigh the bad.

Benatar does not think this is the case. Moving to the right-hand-side, Benatar claims that the absence of pain is good, i.e., preventing pain from being brought into being is a good thing to do. Again, this is fairly uncontroversial. However, Benatar thinks the absence of pleasure is not bad. There are several reasons he thinks this might be the case. A primary reason is that there is no being deprived of that pleasure, nothing has yet been brought into existence.

This is a strong argument and rides on similar intuitions as the Epicurean argument for why death does not harm the being which dies. Yet, most people think that dying will be bad for them, including Benatar. Benatar again claims there is an asymmetry as that which has once lived can be harmed by going back into non-existence (namely by having its interests thwarted), while that which has never existed cannot be harmed.

Benatar thus claims that when evaluating whether to bring X into existence, one cannot count the presence of pleasure that the being will experience as counterbalancing the pain it will experience: the absence of that pleasure would not have been bad, while the absence or prevention of that pain would have been good.

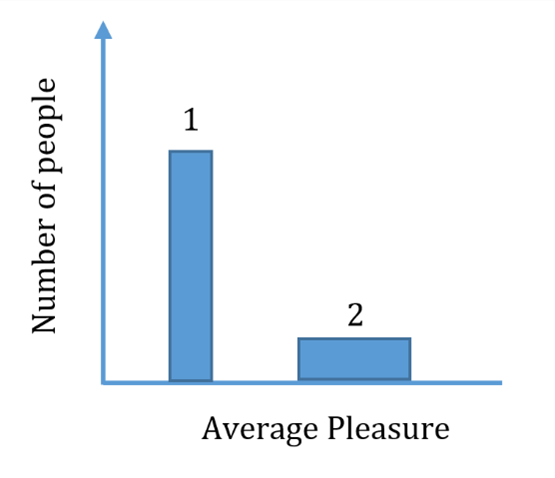

Further evidence for the controversial lower right quadrant can be provided as a proposed refutation of Derek Parfitt’s Repugnant Conclusion. Derek Parfitt claims that consequentialist theories which aim to maximise net pleasure lead to a world few would choose, a repugnant world.24 In Figure 2., there are two possible worlds represented by boxes. The height of the box represents the number of people and the width of the box is the average pleasure of that population. A consequentialist theory that seeks to maximise net pleasure would have to favour the first box, World One, as it has a larger total area than the second box, World Two. However, each person in World One is experiencing a tiny fraction of the pleasure of each person in World Two, and thus the World One inhabitants are on average (at least relatively), close to miserable.

Figure 2.25

Classical Utilitarianism provides few tools to show why we might not want to maximise population size over average welfare, antinatalism does. In the second world, there are far fewer people experiencing pleasure. However, antinatalism says we should not mourn for all those who have not been brought into existence to experience that pleasure, as there is no person deprived. Indeed, on reflection, it seems odd to favour summed utility over average utility once we ask, for whom is the summed utility good? There is no god keeping score. While on the other hand, we can quite easily say who the higher average utility is better for, all those who are experiencing it.

To see how veganism is derived from antinatalism is once again straightforward. Now instead of utilitarianism—claiming that agricultural animals experience net pain during their lives, and this is wrong—the antinatalist need only show that agricultural animals experience any pain. Once this is shown, the asymmetry applies, and that being has been harmed by the suffering they will experience in their lives, without a commensurate gain. Thus, it is wrong to bring that being into existence, ceteris paribus.

Antinatalism, read this way, also applies to our obligations towards wild animals. Unlike many of the tricky problems for the utilitarian about the feasibility of improving the lives of wild animals, we know how to accomplish the antinatalist solution, we do it already. That is, humans have reduced the number of living wild animals on this planet and will continue to do so. For the antinatalist, these future generations never coming into existence will be a good thing. Extinction included.

This is a strawman of antinatalism. Antinatalism per Benatar states that it is unethical to bring a life into existence. As a condition of wildness is that the existence of the animal is not directly due to humans, humans are not directly violating antinatalism in allowing wild animals to reproduce. Indeed, the death of animals, typically required for extinction, is a bad even for the antinatalist:

“Most humans who are concerned about the extinction of non-human species are not concerned about the individual animals whose lives are cut short in the passage to extinction, even though that is one of the best reasons to be concerned about extinction (at least in its killing form)”26

Yet, one could hypothesise that we sterilize animals and thus never take the life away from a sentient being. As antinatalism is underpinned by a theory of value, the addition of the premise that we should act to bring about the good is all that is required for an obligation to sterilize wild animals. This a fortiori with so many generations of suffering on the line; as each generation allowed to live may bring forth many future generations. Moreover, it seems like whatever the harm of death is for the antinatalist, it cannot be worth so many lifetimes of suffering. This gets us back to the conclusion that extinction by almost any means is a net good for the antinatalist.

Yet, Benatar disputes this. Benatar is explicitly not a utilitarian and thus does not endorse a simple calculus of harms. One such principle endorsed by Benatar appears to be that we ought not to murder to accomplish other ends. Whether a synthesis of consequentialist and deontological considerations of this sort is viable, is beyond the scope of this paper. Yet, if we ignore the pragmatic considerations outlined through the proceeding sections, and grant sterilization rather than extermination or euthanasia, we are left with the conclusion that antinatalism endorses a world without wild animals.

Citizenship Theory

The previous sections have shown how hedonic utilitarianism and antinatalism imply fairly radical conclusions about our obligations to wild animals. Yet, these are not exhaustive of the foundations for veganism. Perhaps the most common justification is that consuming animal flesh violates the rights of the animal or animal rights theory (ART). Moreover, and in stark contrast to the previous theories, the most common position regarding wild animals is the injunction to ‘let them be’.

The final theory discussed in this paper seeks to find a reflective equilibrium between these seemingly conflicting positions in less of an ad hoc way than the preceding ART literature. Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka’s citizenship theory seeks to resolve this tension between animal rights and letting wild animals be by asserting that the problem properly understood is one of political philosophy rather than ethics, claiming that differentiated obligations arise depending on the animal’s citizenship category.27

ART states that animals have inviolable basic rights in the same way that humans have universal basic human rights. These rights can be derived through different justifications, but typically rights discourse lies in the Kantian tradition. That is, rights “are a protective circle drawn around an individual, ensuring that she is not sacrificed for the good of others”,28 no matter how large the net good derived from violating her rights could be. Donaldson and Kymlicka, in the tradition of (Rawlsian) liberal egalitarianism, think all animals should be granted these rights before any further considerations of justice.

Thus, ART dictates that bringing animals into existence in order to kill them is wrong in principle. Hence, ART demands veganism. This could entail what seems like a natural extension—that wild animals likewise must have the right not to, e.g., be predated upon or die from starvation. Yet, this again would lead to extensive obligations to wild animals, nowhere near ‘letting them be’. This is where Donaldson and Kymlicka believe a relational theory of justice is required, namely citizenship theory.

According to Donaldson and Kymlicka, citizenship serves three functions in political philosophy:

1) Nationality: “To be a citizen of country X is to have the right to reside in the territory of X, and the right to return to X if you travel abroad”

2) Popular sovereignty: “the state belongs to 'the people', rather than to God or some particular dynasty or caste, and citizenship is about being a member of the sovereign people.”

3) Democratic political agency: “To be a citizen, in this new understanding, is … also to be an active participant in the democratic process (or at least to have the right to engage in such active participation).”

When citizenship is invoked in current discourses, we often presuppose the third definition. In political philosophy, this third definition is further enshrined in contractarian theories or theories which assume a process of public reason or deliberative rationality, such as those of Rawls and Habermas. This can make for a large conceptual leap toward assigning citizenship rights to animals. However, the work of citizenship theory in the domain of the mentally disabled, superseding mere wardship, has gone a long way to dispel these rigid criteria of citizenship. Further, Donaldson and Kymlicka refute that political agency is non-applicable in the case of non-human animals.

In this sense, domestic animals not only have basic rights which must be respected, but as members of our citizenry, they have additional, positive, rights. On the thinnest level, they have the right to reside, as per nationality, but they also have rights in terms of their political agency. Cats demand a wide territory within which to roam. This might be something that the appropriate conception of citizenship would require enshrined in law, such that people cannot purchase or bring a cat into existence without this guarantee. Under this (differentiated) rights theory, this is so even if owning a cat in a small apartment brings about more total utility from the “owner’s” happiness.

This notion of citizenship is quite distinct but related to accounts which attempt to displace the individual as the sole unit of moral concern by showing that even individuals are embedded in wholes or communities which require additional or separate concern.29

So, what then are the implications of citizenship theory for wild animals, and how does it support “letting them be”? First, all animals, including wild animals, are ensured their basic rights. This provides negative protections against, for example, hunting wild animals. Second, wild animals are defined as belonging to a different nationality or citizenry than humans. From this we can derive full sovereignty for wild lands. It is this sovereignty that allows for an extensive obligation to “let them be” while also providing a significantly more nuanced framework with which to interact with wild animals than ART.

Sovereignty is a well-developed, yet disputed, concept in the political philosophy literate. Non-interference, irrespective of a nation’s power, lies at the heart of the concept. However, with tragedies such as the Rwandan Genocide, the concept of the “responsibility to protect” has gathered following, outlining instances where sovereignty cannot justify non-intervention in domestic crimes against humanity. We might then ask why predation and other non-manmade violations of an animal’s basic rights, which the authors grant are ‘lexically prior’,30 do not constitute grounds for violating the sovereignty of natural lands.

In response, the authors first outline a communitarian counterargument: “in the context of ecosystems, food cycles and predator-prey relationships are not indicators of 'failure'. Rather, they are defining features of the context within which wild animal communities exist; they frame the challenges to which wild animals must respond both individually and collectively, and the evidence suggests that they respond competently.” Before turning towards an approach similar to Nusbaum’s capabilities approach: “And if this paternalistic intervention takes place on a broad scale, it is almost certainly going to undermine the ability of wild animals to exercise the capacities and dispositions that evolved precisely in response to their environment.”

Whether these arguments succeed will largely depend on the reader’s acceptance of Kymlicka and Donaldson’s reframing of the issue of wild animal suffering as lying in the domain of political relations rather than personal ethics. Yet, the conclusion of citizenship rights theory accords much closer with most people and vegans’ intuitions regarding our obligations towards wild animals.

Conclusion

This post has explored the implications for wild animals of three ethical theories which obligate veganism. The hedonic utilitarian may have extensive obligations towards wild animals, including promoting their numbers and welfare, limited primarily by epistemic and pragmatic concerns. The utilitarian must further contend with whether wildness provides utility, and whether non-wild environments and animals are demanded by utilitarianism. Antinatalism likely implies that the optimum number of sentient beings, including wild animals, is zero; limited by the interests of currently living creatures, and by whether the theory allows for non-consequentialist considerations. Finally, the differentiated relational obligations of citizenship theory may provide a middle path between animal rights and ‘letting wild animals be’.

References

Arrhenius, Gustaf, Jesper Ryberg, and Torbjörn Tännsjö, "The Repugnant Conclusion", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

Benatar, D. 2001. Why the Naïve Argument against Moral Vegetarianism Really is Naïve. Environmental Ethics. 10 no. 2.

Benatar, D. 2007. Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence, Oxford University Press.

Clare Palmer, “Climate Change, Ethics, and the Wildness of Wild Animals” in B. Bovenkerk and J. Keulartz (eds.), Animal Ethics in the Age of Humans. Blurring boundaries in human-animal relationships. (2016): 131–150.

Cowen, Tyler. 2003. “Policing Nature,” Environmental Ethics 25, no. 2: 169–182.

Bovenkerk, B and Verweij, M. 2006. ‘Between Individualistic Animal Ethics and HolisticEnvironmental Ethics. Blurring the Boundaries’ in B. Bovenkerk and J. Keulartz (eds.), Animal Ethics in the Age of Humans. Blurring boundaries in human-animal relationships. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 369-385.

Cowen, T. 2003. “Policing Nature,” Environmental Ethics. 25, no. 2: 169–182.

Donaldson, S and Kymlicka, W. 2013. Zoopolis, Oxford University Press.

Ebert, R and Machan, T. 2012. “Innocent Threats and the Moral Problem of Carnivorous Animals,” Journal of Applied Philosophy 29, no. 2: 146–159.

Keulartz, J. 2016. “Should the Lion Eat Straw Like the Ox? Animal Ethics and the Predation Problem,” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 29, no. 5: 813–834.

Palmer, C,. 2016. “Climate Change, Ethics, and the Wildness of Wild Animals” in B. Bovenkerk and J. Keulartz (eds.), Animal Ethics in the Age of Humans. Blurring boundaries in human-animal relationships. 131–150.

Pianka, E. R. (1970). On r-and K-selection. The american naturalist, 104(940), 592-597.“Policing Nature,” Environmental Ethics 25, no. 2 (2003): 169–182.

Nagel, T. What Is It Like to Be a Bat? The Philosophical Review. 83, no. 4 (1974): 83(4), 435-450.

Ng, Y. K. Towards welfare biology: Evolutionary economics of animal consciousness and suffering. Biology and Philosophy, (1995). 10(3), 255-285.

Rachels, J. 2004. “Elements of Moral Philosophy”

Rainer Ebert and Tibor R. Machan, “Innocent Threats and the Moral Problem of Carnivorous Animals,” Journal of Applied Philosophy 29, no. 2 (2012): 146–159.

Singer, Peter, Rosinger, David. 1973. "Food for Thought". The New York Review of Books. (1973-06-14).

Rainer Ebert and Tibor R. Machan, “Innocent Threats and the Moral Problem of Carnivorous Animals,” Journal of Applied Philosophy 29, no. 2 (2012): 146–159.

Clare Palmer, “Climate Change, Ethics, and the Wildness of Wild Animals” in B. Bovenkerk and J. Keulartz (eds.), Animal Ethics in the Age of Humans. Blurring boundaries in human-animal relationships. (2016): 131–150.

Nagel, T. What Is It Like to Be a Bat? The Philosophical Review. 83, no. 4 (1974): 83(4), 435-450.

“one simple test of the claim that the pleasure in the world outweighs the pain…is to compare the feelings of an animal that is devouring another with those of the animal being devoured”

Jozef Keulartz, “Should the Lion Eat Straw Like the Ox? Animal Ethics and the Predation Problem,” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 29, no. 5 (2016): 813–834.

Benatar, D, Why the Naïve Argument against Moral Vegetarianism Really is Naïve. Environmental Ethics. 10 no. 2. (2001)

Tyler Cowen, “Policing Nature,” Environmental Ethics 25, no. 2 (2003): 169–182.

Malthusian population dynamics occur as the food or sustenance of a population often grows linearly, while reproduction grows populations geometrically. Thus, without external influences, such as population reductions from predation, populations of wild animals will eventually outstrip their sustenance, leading to a bust in population. These dynamics need not apply to human populations any longer due to technological advances in agriculture.

Pianka, E. R. (1970). On r-and K-selection. The american naturalist, 104(940), 592-597.

This is Parfits sum maximizing consequentialism rather than mean maximizing versions which will be considered in the antinatalism section.

James Rachels, Elements of Moral Philosophy. (2004).

Singer, Peter, Rosinger, David, "Food for Thought". The New York Review of Books. (1973-06-14).

Ng, Y. K. Towards welfare biology: Evolutionary economics of animal consciousness and suffering. Biology and Philosophy, (1995). 10(3), 255-285.

I am not an ecologist; however, this paragraph simply attempts to illustrate a plausible description of the homeostatic equilibrium of ecosystem populations, unavoidably defined by Malthusian dynamics. If it is incorrect in detail, I hope it sill reflects some of the principles at play.

http://highlandswilderness.net/game-management/

The longer the host is alive, typically the better from the point of view of the parasite. The parasite will have an increased chance to reproduce and infect other animals if their host remains alive.

In saying this, the Effective Altruism movement (a utilitarian welfare maximizing movement) often looks to donation opportunities that have little attention paid to them and thus might have the highest marginal benefit per Euro donated. This is due to the diminishing marginal returns to money. Wild animal welfare is surely an under addressed topic, at least for the utilitarian.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2006). Frontiers of justice: Disability, nationality, species membership (p. 130). Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Horns, J., Jung, R., & Carrier, D. R. (2015). In vitro strain in human metacarpal bones during striking: testing the pugilism hypothesis of hominin hand evolution. Journal of Experimental Biology, 218(20), 3215-3221.

Nozick, R. 1974. Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Blackwell Publishers, Oxford. Pg 42.

De Brigard, F. (2010). ‘If You Like it, does it Matter if it’s Real.’ Philosophical Psychology 23(1):43–57.

David Benatar, Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence, Oxford University Press (2007).

Ibid. Pg 38.

Arrhenius, Gustaf, Jesper Ryberg, and Torbjörn Tännsjö, "The Repugnant Conclusion", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

Ibid.

David Benatar, Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence, Oxford University Press (2007). Pg: 197

Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka, Zoopolis, Oxford University Press (2013).

Ibid Pg.20

Bovenkerk and Marcel Verweij , ‘Between Individualistic Animal Ethics and Holistic Environmental Ethics. Blurring the Boundaries’ in B. Bovenkerk and J. Keulartz (eds.), Animal Ethics in the Age of Humans. Blurring boundaries in human-animal relationships. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 369-385.(2006)

A right that must be provisioned before consideration of any other rights.